Late last year, Bruce Willis appeared in an advertisement for Russian mobile phone company MegaFon, and the press blew up with competing stories of whether Willis licensed his likeness to Deepcake, the company that made the commercial, or if it was a unauthorized, unlicensed deepfake. Deepcake reported to the BBC that Willis had “definitely” given his consent “and a lot of materials to make his digital twin,” but Willis’ representatives asserted that the actor had nothing to do with the company and never licensed his image.

Welcome to the world of deepfakes versus digital likenesses. Deepfakes grabbed public attention in the last few years with some astonishing and entertaining videos from the Corridor Crew and a handful of other digital artists, and deepfake apps enabled anyone to create believable, fake likenesses. But concern over the ability of such videos to spread misinformation and worse soon cast a shadow over them. Now though “deepfakes” and “digital likenesses” are often used interchangeably, the former generally refers to an unauthorized use of the likeness of an actor, performer, celebrity or politician, whereas the latter -- also referred to as digital twin, NIL(name, image, likeness) or synthetic media -- implies a legal, licensed, consensual deal.

Holmes Weinberg partner Michael Leventhal points out that NILs were licensed in the music business long before the advent of digital technology, so that record labels could put the artist’s likeness on the album cover. “It always favored the labels and producers putting out the album,” he explains. “It’s always been about the right to market whatever product or service you were selling. But with the advent of digital versions of famous people, it became much more than that.”

Use of digital likenesses in the movie industry became possible at a handful of pioneering visual effects companies such as Digital Domain and Industrial Light & Magic, that did the research and development to make it possible. Digital humans started out as extras in a crowd scene and, as the technology improved, eventually became a digitally enhanced version of lead actors. Consider actors who have been brought back to life or de-aged, including Carrie Fisher and Peter Cushing in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story and Paul Walker in Fast & Furious. In 2018, Star Wars visual effects supervisor Ben Morris revealed that all the lead actors in the franchise are routinely digitally scanned for future use.

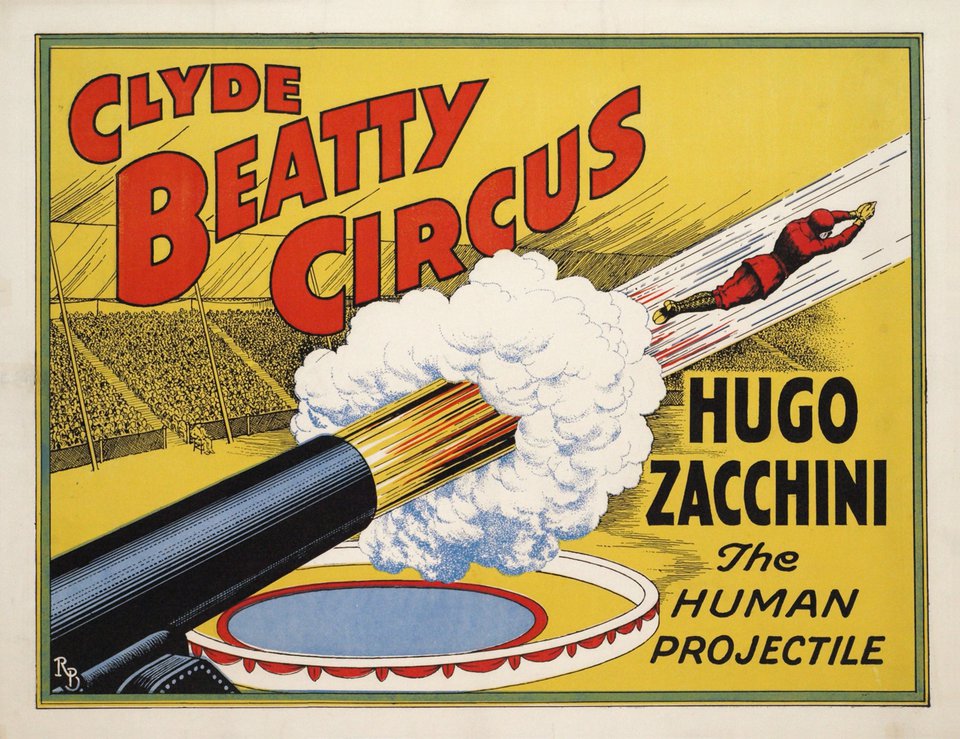

Long before the uncannily realistic Tom Cruise deepfakes went viral, actors and performers have been fighting unauthorized use of their names, images and likenesses. Those struggles led to numerous state laws and a single, 1977 Supreme Court decision -- Zacchini v. Scripps-Howard Broadcasting -- that first codified the Right of Publicity (also known as personality rights), the performer’s ownership of his or her NIL. Circus artist Hugo Zacchini performed a human cannonball act in which he was shot 200 feet from a compressed-air cannon. When a TV journalist showed up at the state fair where he was performing, Zacchini forbade him from filming it. But Zacchini’s 15-second act was broadcast on an Ohio TV station, and the case made it to the Supreme Court.

Since then, recounts Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) senior staff attorney/civil liberties director David Greene, “about 20 states recognize some form of publicity rights, either written into state statues or recognized as common law rights. The lack of consent is typically an element of all the claims,” he continues. “The person suing has to prove they did not consent.” The content of the law varies from state to state. “Some states only allow a lawsuit if the person has created value in their image,” Greene said. “Some are limited to commercial uses including news-like entertainment. It’s not clear if that includes a documentary film or fictionalized version of a public event.”

This patchwork of state laws seems to be holding for now. SAG-AFTRA general counsel Jeffrey Bennett notes that, “we have a good foundation for laws across the country that require consent for the appropriation of someone’s NIL.” He wonders if perhaps “a blatant misappropriation” might trigger “a flood of new legislation,” but points out that, “traditional media companies” value the relationship with performers too much to test the boundaries of existing laws.

In California, Fenwick attorney Kimberly Culp notes that, "this state’s Civil Code 3344 gives a living person a right to commercialize their likeness. The section says that rights recognized under this section are property rights that are defendable,” she says. “Any person who knowingly uses another person’s likeness in any manner would be liable for the damages for the person who owns the right of publicity.” The likeness of a deceased actor or celebrity is also protected under Civil Code 3344 as a property right, Culp adds. In 2022, Forbes annual list for the most highly compensated deceased celebrities included DavidBowie ($250 million), Elvis Presley ($110 million) and, in the No. 2 spot, Kobe Bryant ($400 million); the dollar amount has exploded since the first list in 2001.

Although some argue for a federal Right to Publicity law, EFF’s Greene warns against how it could be used to restrict free speech. An expanded Right of Publicity law, he says, “really allows for potentially very wide control of when someone can be depicted by anyone else … even if it’s of historical record or public interest. There would be no work based on a true story,” he points out.

Videogames are another venue where professional athletes have been licensing their NILs for some time, and collegiate athletes most recently won a battle to have the Right of Publicity expanded to include their NIL rights. Ten years ago, they challenged the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA), which had been licensing student-athletes’ names, images and likenesses for use in video games without their consent or compensation. Bennett reports that SAG/AFTRA wrote amicus curiae briefs to support the early cases of student athletes claiming NILs rights. “We knew immediately when we saw these video games that the technology would get better and it wouldn’t just be video games digitally exploiting athletes, actors and sound recording artists,” he says. “Before you even talk about licensing and its parameters, central to us is the concept of consent.”

“The video games are undeniably protected by the First Amendment,” says Bennett, who notes that the studios also make claims of First Amendment rights. “But you have to balance the right of publicity against that. We feel the same way about digital avatars in traditional media, but it hasn’t yet played out in a legal arena.” Actors who are now proactively scanning themselves for future licensing work with their representatives to negotiate the terms. “It’s a new world order negotiating those terms,” says Bennett. “These are brand new concepts in right of publicity bills, and our membership needs to be very educated about the difference between a good and bad deal.” Deal terms going forward, he reports, will be negotiated in collective bargaining agreements with the

Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) and the Joint Policy Committee (JPC) that represents advertisers and advertising agencies. “We know from technology that any raw material – even if it’s just your voice – can be replicated without you,” Bennett adds. “Not all traditional media companies are doing it yet, but tech companies are showing people how they can do it and talking to the studios about how they can work together.”

With the rise of the metaverse and Web 3.0, the possible uses for legitimate use or misuse of NILs have exploded. No wonder, then, that agency CAA announced its first-ever chief metaverse officer. Suppressing deepfakes may be a game of whack-a-mole. But, the savvy performer, the devil is – for now and the foreseeable future - in the details of the licensing deal hammered out by his or her gatekeepers.