Over the last 40 years, staging and projection industry veteran Josh Weisberg has helped create some of the most innovative, immersive and artistic examples of large-screen display installations in the world. Having served as president and co-founder of his namesake Scharff Weisberg as well as its successor, WorldStage, Weisberg has led the way to innovative deployments for clients including Prada’s retail store in lower Manhattan, the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, NY, and the 40th anniversary special broadcast of Saturday Night Live. Among other envelope-expanding projects, Weisberg helped develop innovative ways to exhibit video art in outdoor environments including Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art, the cylindrical façade of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and surrounding buildings. For MoMA, Weisberg engineered a multi-screen arthouse in midtown Manhattan, projecting elements of artist Doug Aitken’s sleepwalkers video installation on eight different walls at sizes ranging from 40 to 65 feet wide. Weisberg says that kind of scale can be important to artists. “The freedom of working electronically means you can reach a much larger audience on site,” he explains. “You could reach a similar size if you painted a big mural or did the kind of large-scale photography that JR does — but not in an animated visual medium.”

Weisberg has retired from his position at the helm of WorldStage but continues to work with some of his longstanding clients in the arts, events, broadcast and industry as a business and technology consultant through his new company, Navolo Audio+Video. Over the years, LED displays and video walls have largely replaced video projections for big-screen video productions, though Weisberg says he still appreciates the “cinematic qualities” of video projection. But he acknowledges that LED screens are the more practical technology—largely because they have a much smaller footprint than projector-and-screen systems. “One of the other advantages [of LED] is not so much the video quality, but the quality of the environment you can create with other things like lighting,” he explains. “It can be indoors, it can be outdoors, you can have 100 theatrical lights surrounding it, and it doesn’t matter because you can still see the screen.”

Weisberg points to film production as one of the markets for state-of-the-art LED screen installations, where they are used to create digital backdrops that look like photoreal environments for productions like the Disney+ series The Mandalorian. The effect is targeted at viewers watching the finished show at home, but Weisberg says LEDs can create a convincing illusion of space in person, as well. “You can create an entire room — floors, ceiling and walls — with LEDs,” he says. “In the more sophisticated VR studios, that’s what they are doing. It’s a tremendous aid for performers, allowing them to have a much more natural and less rehearsed filming process than a typical green-screen set.”

During the pandemic, immersive, LED-driven environments have found new applications in the corporate world, where firms observing social distancing measures have looked to 3D environments to replace in-person meetings with journalists. Weisberg describes a recent product launch for a “Fortune 100 tech company” that used background LED walls and an LED floor to create a 3D environment that resembled one of their laboratories. Real pieces of furniture holding examples of the new products were placed onto the LED floor, giving the live presenters physical objects to interact with.

“It’s one way to create spontaneity,” Weisberg explains. “They don’t like to film these things in advance, because of the danger of a security lapse. They like to do them live and in a controlled environment, and a virtual set allows that to happen.”

The production becomes more complicated if the company wants to have two people who are geographically separate appear as though they are together in the same place. Weisberg suggests that the recent Golden Globes could have been an excellent test case for such a scenario, though it would be difficult to pull off. “Think about the camera capturing the images—two cameras [in two different locations] would have to work in absolutely synchronous fashion,” he says. “You’d have to build two identical environments with two identical backgrounds and have two identical cameras moving in an identical fashion so you could join those two images live, in real time. Theoretically, it’s possible, but I’m not aware of anyone who’s actually done it.”

But what if you could use a “hologram” to make someone seem to appear on a faraway stage in three dimensions? That’s how a life-size, fully animated Tupac Shakur is said to have made a surprise appearance at the 2012 Coachella Valley Music and Arts festival, apparently dancing and rapping on stage with Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg. The performance saturated the entertainment media and put the words “Tupac hologram” on everyone’s lips.

The biggest problem with the Tupac “hologram” is that, well, it’s not a hologram. Tupac’s appearance on stage relies on a creaky theatrical illusion originally popularized in the 1860s called “Pepper’s ghost.” It uses the reflection of an image hidden below or beside the stage — say, a brightly lit actor or actress — onto a glass screen installed at the appropriate angle and position to give the impression that the figure has appeared in front of an audience. In the 19th century, Victorian scientist John Henry Pepper used engraved silvered glass to reflect ghostly figures back to the audience; Coachella’s Tupac, a CG figure created at Digital Domain, was projected onto Mylar foil, which made the image seem somewhat brighter and more solid. (Read Holowire’s previous coverage of Digital Domain’s work with digital humans.)

“My son was actually at the Coachella performance where they brought out virtual Tupac. There was obviously a huge groundswell of interest after that. My son said, ‘Dad, you have to remember that it’s an audience of 55,000 people and most of them are standing really far from the stage. Plus, everybody’s on drugs.’”

Weisberg lets that observation hang in the air for a second before continuing, “If I could do a corporate product reveal where the entire audience was on drugs, I could do a better job with Pepper’s ghost,” he says. “I always try and temper the client’s expectations. It never looks as good as they think it’s going to.”

What are the alternatives? If a truly holographic display panel, such as a light-field display, could be incorporated into a stage set or consumer space, the live appearance of a celebrity or corporate executive could be made more complete and more convincing. “People have tried to do live telepresence with holograms — really Pepper’s ghost,” Weisberg says. “If large-scale light-field displays become a reality, that desire is still there, and it can be supported by something that does it more effectively.”

Weisberg remembers his own trials with Pepper’s ghost. Worldstage created an installation at the U.S. Open Tennis Championships for a corporate client that involved a constructed locker room where people could “meet” a tennis star who appeared before them thanks to a modified Pepper’s ghost effect. “I think we got away with it,” he says. “But if it were a larger-scale light-field display, cleverly built into the scenic environment? Think how effective that might be.”

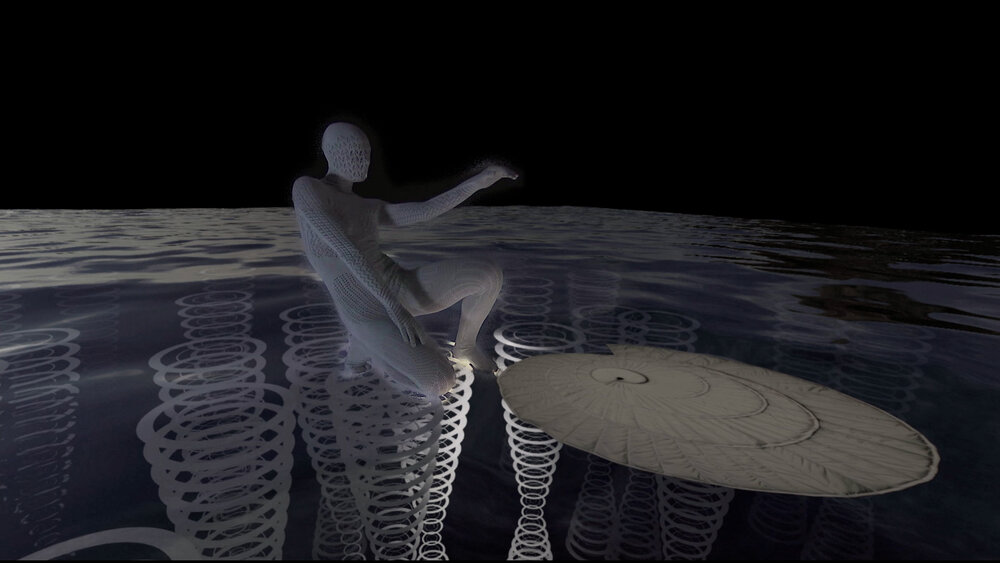

Another benefit of light-field technology is that a camera can focus on the image itself rather than the display surface; photographically, the light-field image looks and behaves just like a real object, meaning depth-of-field, perspective and other characteristics should mesh seamlessly with the real environment surrounding the light-field display. “What if there were real-time light-field displays that allowed a presenter to interact with a 3D-seeming object that could be captured in camera in a realistic fashion?” Weisberg asks. “They could manipulate the object, orbit the object, zoom in and zoom out, maybe pull it apart. And if there is a live audience, they’ll see it as well.”

With the COVID pandemic presumably on the wane, Weisberg sees new applications for virtual environments. He cites museum exhibits as a possible fit, pointing to the slew of immersive Vincent van Gogh experiences that are launching this year in a number of cities across the U.S. (The New York Times reports that a half-dozen different companies are producing their own immersive van Gogh shows, calling the artist “the rock star of this genre.”) He also notes the burgeoning market for NFTs, collectible pieces of digital art recorded as assets on a blockchain. “The idea of having a light field on your wall in your living room with some kind of pointing device that allows the viewer to manipulate and explore the artist’s 3D creation in real time has some power,” Weisberg speculates. (Learn more about NFTs in our coverage of the new market for digital artwork.)

Though he’s not sure where light-field displays will find their most natural fit, Weisberg is convinced VR or AR headsets won’t be the ultimate solution for immersive environments, especially where group experiences are concerned. “I’ve been involved with some events where we’ve used it,” he says. “It kind of worked — if you were sitting down. How does light-field technology help solve some of those problems? That’s something we have to look at carefully once the technology becomes available in large display sizes.”

And Weisberg notes some important caveats when it comes to how holographic screens can be deployed, including the amount of computing power required to drive them and the issue of uniformity. “One of the things they found early on with LED screens in virtual environments is that they have a tendency to drift a bit,” he says. “Your eye can’t see it but the camera can and the colorist can.”

Weisberg says the key to future innovation will require artists, designers and system integrators to be wary of new and unproven systems and processes while still remaining open to and interested in new ways of accomplishing goals. “After a career that spans close to 40 years, I still find new things to discover and new ways of doing things,” he says. “It’s a matter of keeping your mind open and being respectful of legacy but not letting it rule your practical life — your real life.”